The flickering neon sign of a forgotten internet cafe cast long shadows. In the digital alleyways, whispers of vulnerabilities circulate like contraband. Today, we’re not just dissecting code; we’re dissecting the very language of our adversaries. We’re tracing ghosts in the machine, understanding how a simple, yet devastating, web flaw got its notorious moniker: Cross-Site Scripting. This isn't about exploiting; it's about understanding the roots of the threat to build impenetrable defenses. Let's peel back the layers of hacker etymology.

The moniker "XSS" itself is a piece of hacker lore, a testament to the often cryptic and shorthand-driven communication within the security underground. But why "XSS" and not just "CSS" or "X-Site Scripting"? The answer lies in a history of clever wordplay, evolving threat landscapes, and the very real need to differentiate attacks from legitimate styling techniques. This isn't just an academic exercise; understanding the origin story of XSS provides crucial context for its evolution and the defensive strategies we employ today.

The Genesis of a Weakness: Early Web Vulnerabilities

Before we delve into the nomenclature, let's set the stage. The early days of the World Wide Web were a wild frontier. Websites were static, and the dynamic interactions we take for granted today were nascent. Developers, eager to create more engaging user experiences, began incorporating client-side scripting, primarily JavaScript, to add interactivity. This innovation, while groundbreaking, also unknowingly opened Pandora's Box.

"The code you write reflects your current understanding. The security of the code reflects your understanding of how others will break it." - A principle etched in silicon.

Early issues often revolved around how browsers handled data that was supposed to be static but could be manipulated. The concept of injecting malicious scripts into a webpage, one that would then execute in the *user's* browser, was a paradigm shift. This wasn't about crashing a server; it was about hijacking a user's session, stealing their data, or manipulating their interaction with a trusted website.

The "Hotmail Attackments" and the Breeding Ground

A significant inflection point in the popularization and understanding of XSS-like attacks can be traced back to incidents like the "Hotmail Attackments" in the late 1990s. While the exact technical details are often complex and debated in hacker circles, the core idea was that malicious code could be delivered through seemingly innocuous email attachments or links, exploiting vulnerabilities in how webmail clients rendered content. This highlighted how an attacker could leverage a trusted platform (like Hotmail) to propagate attacks to its users.

These early incidents, often occurring on massive platforms with millions of users, served as stark warnings. They demonstrated that the attack surface wasn't limited to traditional software but extended to the very fabric of how users interacted with web applications. The web, it turned out, was a fertile breeding ground for new kinds of social engineering and client-side attacks.

The Naming Convention: Why "XSS"?

The term "Cross-Site Scripting" itself is attributed to programmer Chris Shiflett, though the underlying vulnerability was recognized earlier. The crucial element was the "cross-site" aspect. An attacker wouldn't necessarily need to compromise the target server directly. Instead, they could host malicious code on their own domain, or leverage another vulnerable site, causing it to execute scripts within the context of a *different*, trusted website's origin. This meant a script hosted on `attacker.com` could execute as if it originated from `yourbank.com`.

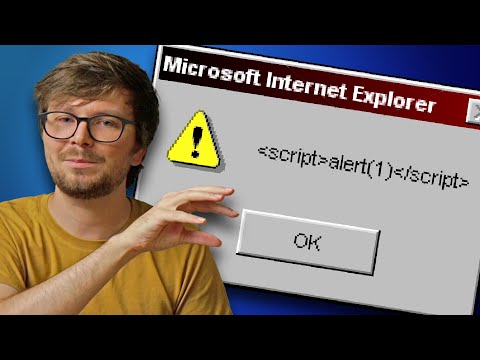

The "XSS" abbreviation emerged as a way to distinguish this from "CSS" (Cascading Style Sheets), another common web technology. The "X" acts as a placeholder for the "Cross" in Cross-Site. This shorthand became standard in security advisories and hacker communities. It was a concise, easily recognizable identifier for a specific class of vulnerabilities.

"Inventing a name is often the first step in understanding a problem. 'XSS' gave a label to a danger that was lurking in the shadows of the early web."

The CERT Advisory CA-2000-02, issued by the Computer Emergency Response Team in 2000, played a significant role in formalizing the threat and the terminology. This advisory discussed the dangers of "Cross Site Scripting" attacks, detailing how they could be used to circumvent browser security mechanisms like the Same-Origin Policy.

The Evolution of XSS: From Simple Scripts to Complex Attacks

What started as relatively simple injection of alert boxes has evolved into sophisticated attacks. Modern XSS vulnerabilities can be used for:

- Credential Theft: Capturing session cookies or form submissions.

- Phishing: Injecting fake login forms into legitimate websites.

- Malware Distribution: Redirecting users to malicious sites or triggering drive-by downloads.

- Website Defacement: Altering the appearance or content of a website.

- Session Hijacking: Taking over a user's active session with a website.

The type of XSS (Stored, Reflected, DOM-based) further refines our understanding, each with unique vectors and mitigation strategies. A Stored XSS, for instance, is baked into the website's data, while a Reflected XSS is returned in a server's response to a specific request, often from a malicious link.

Defensive Strategies: Building the Shield

Understanding the etymology and history of XSS is not merely an academic curiosity; it's a foundational element of robust cybersecurity. To defend against XSS, we must think like the adversary who named it – with precision, clarity, and foresight.

Taller Práctico: Fortaleciendo tus Aplicaciones Web contra XSS

- Input Validation: The first line of defense. Sanitize and validate *all* user input. Assume any data coming from the client is malicious until proven otherwise. Use allow-lists for expected characters and formats rather than block-lists.

- Output Encoding: Properly encode any data that is rendered within an HTML context. This tells the browser to treat the data as text, not as executable code. Tools and libraries for various programming languages can assist significantly here.

- Content Security Policy (CSP): Implement a strong CSP header. This allows you to specify which sources of content (scripts, styles, images) are trusted and allowed to be loaded. A well-configured CSP can drastically limit the impact of even a successful XSS injection.

- Web Application Firewalls (WAFs): While not a silver bullet, WAFs can detect and block many common XSS attack patterns. However, they should be used as a supplementary defense, not the sole measure.

- Regular Auditing and Penetration Testing: Proactively hunt for XSS vulnerabilities. Utilize automated scanners, but more importantly, conduct manual code reviews and penetration tests to uncover logic flaws that scanners might miss.

The battle against XSS is ongoing. As web technologies evolve, so do the attack vectors. Staying informed about the latest XSS techniques and incorporating them into your defensive simulations is critical.

Veredicto del Ingeniero: ¿Vale la pena entender la etimología?

Absolutely. Understanding the origin of a threat like XSS provides invaluable insight into its fundamental nature. It illuminates the mindset of attackers, the historical context of web security evolution, and why certain defensive measures are paramount. It's the difference between treating a symptom and curing the disease. For any security professional aiming to truly understand and defend against web vulnerabilities, delving into their history and naming conventions isn't optional; it’s a prerequisite for expertise.

Arsenal del Operador/Analista

- Tools: Burp Suite (Pro for advanced scanning), OWASP ZAP, Browser Developer Tools, KQL (for log analysis), Python (for custom scripting).

- Books: "The Web Application Hacker's Handbook," "Real-World Bug Hunting: A Field Guide to Web Hacking."

- Certifications: OSCP (Offensive Security Certified Professional) for offensive understanding, CISSP for broader security principles.

- Resources: OWASP Top 10, PortSwigger Web Security Academy.

Preguntas Frecuentes

- What is the primary difference between XSS and CSRF?

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) injects malicious scripts into a trusted site, executing in the user's browser. Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) tricks a user's browser into making an unwanted request to a trusted site.

- Can XSS affect non-browser clients?

- While primarily a browser vulnerability, the principles of script injection can apply to other client applications that render HTML or execute code based on external input.

- Is XSS still a relevant threat in modern web development?

- Yes. Despite advancements in frameworks and defenses, XSS remains one of the most common and impactful web vulnerabilities due to developer error and evolving attack vectors.

El Contrato: Asegura el Perímetro de tu Aplicación

Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to conduct a mini-audit of a simple web application (a deliberately vulnerable one, like DVWA or OWASP Juice Shop in a safe, isolated environment). Your goal is to identify one instance of Reflected XSS and one instance of Stored XSS. Document the payload used on the attacker's side and the successful execution in the victim's browser. Then, propose the specific defensive coding changes (input validation and output encoding) that would mitigate each vulnerability you found. Report your findings and proposed fixes in the comments below.

No comments:

Post a Comment